Now it’s very rare for boxing fans to get genuinely excited about a major fight card. The preliminaries to big matchups are often exercises in tedium, as fans endure a series of largely pointless matches, matches invariably offering limited talent or minimal excitement, or both.

But that was not the case in 1920 in Benton Harbor, Michigan, when three of the best who ever laced up their gloves entered the ring, one after another. In fact, in terms of an array of legendary in-ring talent, it remains perhaps the best card ever put together. No one at the time could have fully appreciated how special the event was, but that’s completely understandable. In terms of elite, Hall of Fame pugilists, fight fans in the 1920s were spoiled.

First, the immortal Sam Langford, arguably one of the best boxers of all time, pound for pound, and possibly the best to never win a world title. For Benton Harbor fans, Langford faced Big Bill Tate in a tight six-round fight. In 1920, and for more than a decade afterward, “The Color Line,” as they liked to call it (the phrase sounds better than “The Bigotry Line” or “The KKK Line”), was closely watched because of the trauma. that Jack Johnson’s championship reign had inflicted on white America. As a result, black and white heavyweights rarely squared off; it was too stressful for everyone.

Langford and Tate were, like Harry Wills, Joe Jeannette, Jeff Clark and Sam McVea, in a group of highly talented black heavyweights who were never given the opportunities they deserved and instead were forced to fight each other repeatedly. , a kind of Negro Boxing League, so to speak. Tate was a huge heavyweight for the time, standing over six and a half feet tall and weighing over 220 pounds. He was also one of Jack Dempsey’s favorite sparring partners.

Tate and Langford ultimately fought ten times and this was their sixth meeting. Langford ended up winning the series with five wins to four losses and a tie, but the fact that Langford won any of his contests is a clear testament to the in-ring genius of “The Boston Terror” as it gave Tate huge advantages in height, reach and weight. . This time around, the paper’s six-round decision went to Tate “by a pinch,” according to Bismarck and the Chicago Tribunes.

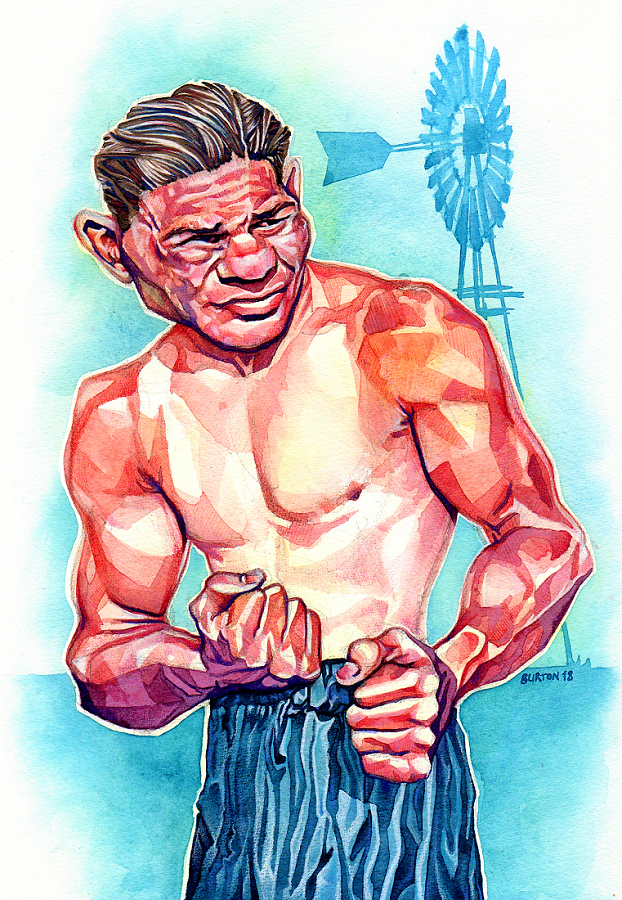

Next up is the great Harry Greb, arguably the greatest middleweight of all time and one of the top ten boxers of all time, pound for pound. His opponent, Chuck Wiggins, aka “The Hoosier Playboy,” was no pushover either. Wiggins proved to be a durable heavyweight, giving greats Tommy Loughran and Gene Tunney tough battles before he was done. He faced “The Smoke City Wildcat” at least eight times and while Wiggins never came close to defeating the great Greb, he gave him more than a little trouble on a few occasions and this was one of them.

For this meeting, Wiggins tried out a new strategy for taking on the human threshing machine that was Greb: recklessly jumping on his opponent and throwing wild swings to prevent Greb from imposing his trademark whirling, swarming style. He preoccupied Harry for about three rounds before he began timing his biggest opponent and finding opportunities to attack. The last few rounds belonged to “The Pittsburgh Windmill” and the smaller man once again proved himself superior. As we all know, Greb would go on to establish himself as one of the greatest of all time before his untimely death in 1926. Less well known is the fact that “The Hoosier Playboy” struggled for another decade before embarking on a long career of exciting fights with the Indianapolis Police.

Finally, the main event: Jack Dempsey defending, for the first time, the heavyweight title he had taken from Jess Willard more than a year earlier. His opponent was Billy Miske and the fight was nothing exceptional, although the story behind it is. “The Manassa Mauler” knocked down “The St. Paul Thunderbolt” three times, the last for the count in the third round. These were the first takedowns of Miske’s career, but his sudden vulnerability wasn’t entirely due to Dempsey’s thunderous power.

Miske’s terrible secret was that he was slowly dying of kidney failure, but he had to keep fighting to pay off his debts and provide for his family. He had been diagnosed two years earlier, and although there were rumors of his deteriorating health, the sad truth would not come to light until after Miske’s death. Incredibly, Miske would have another 23 games after this loss, winning all but two, before he finally succumbed on New Year’s Day 1924. “Billy Miske and Benton Harbor,” Dempsey would later say. “Well, I wish it had never happened.”

That Labor Day card was the first of many hugely successful events engineered by Dempsey’s team, his manager Jack Kearns and promoter genius Tex Rickard. Together, over the next few years, they made loads of money. But one of the most intriguing facets of this event was how it renewed talk of a Dempsey vs. Greb showdown, a dream matchup if there ever was one, and a clash that probably would have been as big as the following year’s Dempsey vs. Carpentier battle. . , the first door of a million dollars.

And yet the fight never took place. No one will know for sure why this dream fight never happened, but one fact that cannot be glossed over is that a few days before the Benton Harbor card, in an attempt to further build interest, Greb and Dempsey discussed several rounds. . for the public. As reported by no less an authority than The New York Times: “Dempsey could do very little with the speedy light heavyweight, while Greb seemed to be able to pummel Dempsey almost at will.”

And yet, who knows, it’s very likely that, given the opportunity, Sam Langford would have beaten them both. (In fact, Dempsey is on record as stating that Langford “probably would have knocked me out.”) Or Dempsey might have been too much for Langford. Or Greb would have overwhelmed the other two, we can only speculate. Three all-time greats and a trio of incredible matches that unfortunately never happened. The next best thing took place over a century ago when the three legends of the ring competed on the same September afternoon. —Michael Carbert